Jeremy Brett

| Jeremy Brett | |

|---|---|

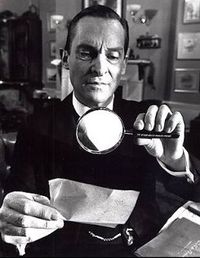

Jeremy Brett in the role of Sherlock Holmes. |

|

| Born | Peter Jeremy William Huggins 3 November 1933 Berkswell Grange in Berkswell, Warwickshire, England |

| Died | 12 September 1995 (aged 61) London, England |

| Years active | 1954 - 1995 |

| Spouse | Anna Massey (1958 - 1962) (divorced) Joan Wilson (1976 - 1985) (her death) |

Jeremy Brett (3 November 1933 – 12 September 1995), born Peter Jeremy William Huggins, was an English actor, most famous for his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes in four Granada TV series.

Contents |

Early life

Peter Jeremy William Huggins was born at Berkswell Grange in Berkswell in late 1933.[1] He was the son of a Lord Lieutenant of Warwickshire and an heir of the Cadbury chocolate family. Educated at Eton, he claimed to have been an "academic disaster", attributing his learning difficulties to dyslexia. However, he excelled at singing and was a member of the college choir. He became a drama student, but his father demanded that he change his name for the sake of the family honour.[2]

Theatre

Brett trained as an actor at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London.[3] He made his professional acting debut at the Library Theatre in Manchester in 1954, and made his London stage debut with the Old Vic company in Troilus and Cressida 1956.[4] In the same year he appeared on Broadway as the Duke of Aumerle in Richard II.[5] He went on to play many classical roles on stage, including numerous Shakespearean parts in his early career with the Old Vic and later with the Royal National Theatre. Brett also played Sherlock Holmes on stage.

Television

From the early 1960s, Brett was rarely absent from British television screens. He starred in many serials, notably as d'Artagnan in the 1966 adaptation of The Three Musketeers. A few of his appearances were in comedic roles, but usually with a classic edge, such as Captain Absolute in The Rivals. In 1973, Brett portrayed Bassanio in a televised production of William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, in which Laurence Olivier portrayed Shylock and Joan Plowright Portia. (Brett, Olivier and Plowright had previously played the same roles in a Royal National Theatre production of the play.) Brett joked that, as an actor, he was rarely allowed into the 20th century and never into the present day. In reality, several of his early television appearances, in ITC series such as The Baron and The Champions saw him cast as swarthy, smooth villains very much in the present.

Film

Although Brett's feature film appearances were relatively few, he did play Freddie Eynsford-Hill in the 1964 blockbuster film version of My Fair Lady. His singing voice was dubbed in the film, but Brett could still sing, as he later proved when he played Danilo in The Merry Widow on British television in 1968.

Brett was briefly considered by Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli for the role of James Bond in On Her Majesty's Secret Service after Sean Connery quit the series in 1967, but the role went to Australian George Lazenby instead. A second audition for the role of 007 for Live and Let Die was also unsuccessful, and Roger Moore won the coveted part.

Jeremy Brett's final, posthumous on-screen appearance was an uncredited bit part as "Artist's Father" in Moll Flanders, a 1996 Hollywood feature film starring Robin Wright Penn in the title role. The film (not to be confused with the 1996 ITV adaption starring Alex Kingston) was released nearly a year after Brett's death.

Notable in all of Jeremy Brett's roles is his precisely honed diction. Brett was born with a speech impediment, "rhotacism", that kept him from pronouncing the "R" sound correctly. Corrective surgery as a teenager, followed by years of practising, gave Brett an enviable pronunciation and enunciation. He later claimed that he practised all of his speech exercises daily, whether he was working or not.

As Sherlock Holmes

Although he appeared in many different roles during his 40-year career, Brett is now best remembered for his performance as Sherlock Holmes in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, a series of Granada Television films made between 1984 and 1994. These were adapted by John Hawkesworth and other writers from the original stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Even though he reportedly feared being typecast, Brett appeared in 41 episodes of the Granada series, alongside David Burke and, latterly, Edward Hardwicke as Dr Watson.

After taking on the demanding role, Brett made few other acting appearances, and he is now widely considered to be the definitive Holmes of his era, just as Basil Rathbone was during the 1940s. Brett had previously played Doctor Watson on stage opposite Charlton Heston as Holmes in the 1980 Los Angeles production of The Crucifer of Blood, making him one of only three actors to play both Holmes and Watson professionally (the other two are Reginald Owen, as Watson in the 1932 film Sherlock Holmes and Holmes in 1933's A Study in Scarlet, and fellow Old Etonian Patrick Macnee, who played Watson first in 1976's Sherlock Holmes in New York and Holmes in 1993's The Hound of London).

Brett had been approached in February 1982 by Granada TV to play Holmes. The idea was to make a totally authentic and faithful adaption of the character's best cases. Eventually Brett accepted the role. He wanted to be the best Sherlock Holmes the world had ever seen.[6] He conducted extensive research on the great detective and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself, and was very attentive to discrepancies between the scripts he had been given and Conan Doyle's original stories.[7] One of Brett's dearest possessions on the set was his 77-page "Baker Street File" on everything from Holmes' mannerisms to his eating and drinking habits. Brett once explained that "some actors are becomers — they try to become their characters. When it works, the actor is like a sponge, squeezing himself dry to remove his own personality, then absorbing the character's like a liquid".[8]

Brett was obsessed with bringing more passion to the role of Holmes. He introduced Holmes' rather eccentric hand gestures and short violent laughter. He would hurl himself on the ground just to look for a footprint, he would leap over furniture or jump on the parapet of a bridge with no regard for his own personal safety.

Holmes' obsessive and depressive personality fascinated and frightened Brett. In many ways Holmes' personality resembled Brett's own, with outbursts of passionate energy followed by periods of lethargy. It became difficult for Brett to let go of Holmes after work. He had always been told that the only way for an actor to stay sane was for him to leave his part behind at the end of the day, but Jeremy started dreaming about Holmes, and the dreams turned into nightmares.[9] Brett began to refer to Sherlock Holmes as "You Know Who" or simply "HIM": "Watson describes You Know Who as a mind without a heart, which is hard to play. Hard to become. So what I have done is invent an inner life".[10] Brett invented an imaginary life of Holmes to fill the hollowness of Holmes' "missing heart", his empty emotional life. He imagined :"...what You Know Who's nanny looked like. She was covered in starch. I don't think he saw his mother until he was about eight years old..." etc..[11]

Eventually it began to go wrong. His workload was pushing him to the limit. While the other actors disappeared to the canteen for lunch Jeremy would sit alone on the set reading the script, looking at every nuance.[12] He would read Holmes in the weekends and on his holidays. "Some actors fear if they play Sherlock Holmes for a very long run the character will steal their soul, leave no corner for the original inhabitant", he once said.[13] It never occurred to him that he was ill.

Personal life

Brett was bisexual, but intensely private. On 24 May 1958 he married his first wife, the actress Anna Massey (daughter of Raymond Massey), but they divorced in 22 November 1962 after she claimed he left her for another man.[14][15] Their son, David Huggins, born in 1959, is a British cartoonist, illustrator and novelist.[16] Brett then married Joan Sullivan Wilson in 1976, but who died of cancer in July 1985[17] shortly after Brett had finished filming Holmes’ "death" in "The Final Problem". Brett also enjoyed a close relationship with the actor Gary Bond[18].

Illnesses and death

After the death of Joan Wilson, Brett struggled with filming the third Granada series, The Return of Sherlock Holmes in late 1985. On the set it was noticed that his manic episodes, his excessive changes of mood, were getting worse and eventually grief and workload became too much; he had a breakdown, was hospitalised and diagnosed manic-depressive.

Jeremy Brett was given lithium tablets to fight his manic depression. He knew that he would never be cured; he had to live with his condition, look for the signs of his disorder and then deal with it.[19] He wanted to go back to work, to play Holmes again. The first episode to be produced after his discharge was a two-hour adaption of The Sign of the Four. From then on the difference in Brett's appearance slowly became more noticeable as the series developed. One of the side effects of the lithium tablets was fluid retention. Brett began to look and act differently. The drugs were slowing him down; he was putting on weight and retaining water.[20] Brett also had heart troubles. His heart was twice the normal size,[21] he would have difficulties breathing and would need an oxygen mask on the set. "But, darlings, the show must go on", was his only comment.[22]

During the last decade of his life, Brett was treated in hospital several times for his mental illness, and his health and appearance visibly deteriorated by the time he completed the later episodes of the Sherlock Holmes series. During his later years, he discussed the illness candidly, encouraging people to recognise its symptoms and seek help.

Brett died on 12 September 1995 at his home in Clapham, London, from heart failure. His heart valves had been scarred by rheumatic fever contracted as a child.[23]

Mel Gussow wrote in a New York Times obituary "Mr. Brett was regarded as the quintessential Holmes: breathtakingly analytical, given to outrageous disguises and the blackest moods and relentless in his enthusiasm for solving the most intricate crimes."[24]

Quotations

"Holmes is the hardest part I have ever played — harder than Hamlet or Macbeth. Holmes has become the dark side of the moon for me. He is moody and solitary and underneath I am really sociable and gregarious. It has all got too dangerous".[25]

Filmography

- Svengali (1954)

- War and Peace (1956) as Nikolai Rostov

- The Very Edge (1962)

- The Wild and the Willing (1962)

- Girl in the Headlines (1963)

- Act of Reprisal (1964)

- My Fair Lady (1964) as Freddy Eynsford-Hill

- Nicholas and Alexandra (1971)

- A Picture of Katherine Mansfield (1973)

- The Medusa Touch (1978)

- Mad Dogs and Englishmen (1995)

- Moll Flanders (1996)

See also

- List of actors who have played Sherlock Holmes

References

- ↑ http://www2.freebmd.org.uk/cgi/information.pl?scan=1&r=167020703&d=bmd_1279003032

- ↑ Sheridan Morley (April 27, 1997). The curse of being Conan. The Sunday Times. p. 5

- ↑ Who's Who in the Theatre, 17th ed. Gale Research, 1981.

- ↑ Some Joe You Don't Know: An American Biographical Guide to 100 British Television Personalities, by Anthony Slide, Greenwood Press, 1996

- ↑ Contemporary Theatre, Film, and Television, Volume 15. GALE, 1996

- ↑ Terry Manners, The Man Who Became Sherlock Holmes - The Tortured Mind of Jeremy Brett, Virgin Publishing Ltd., London, 2001, ISBN 0 7535 0536 3.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 122.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 217.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 121.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 134.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 134.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 133.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 216.

- ↑ Massey, Anna (2006). Telling Some Tales. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-179645-8

- ↑ David Stuart Davies, Dancing in the Moonlight: Jeremy Brett, London, 2006

- ↑ "David Huggins: Public faces in private places - Features, Books - The Independent". The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/david-huggins-public-faces-in-private-places-747515.html. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 144.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 130.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 160

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 204.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 26.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 207.

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 26.

- ↑ "Jeremy Brett, an Unnerving Holmes, Is Dead at 59" by Mel Gussow, The New York Times, September 14, 1995, p. B15

- ↑ Terry Manners, p. 212.

External links

- Jeremy Brett at the Internet Movie Database

- Jeremy Brett biography and credits at the British Film Institute's Screenonline

- Interview with Jeremy Brett at NPR.org